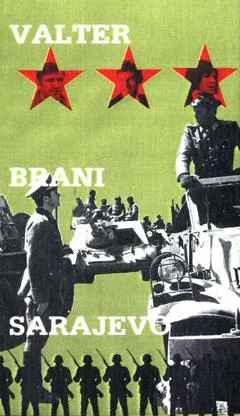

Walter Defends Sarajevo (1972)

In the Baščaršija neighborhood of the Stari Grad municipality of Sarajevo, near the iconic Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque, the Sarajevo clock

To say that the Balkans sit squarely on the fault line between east and west would be an understatement.

Ever since Constantine the Great, born in what is now Niš in modern day Serbia, and Diocletian, who retired to what is now Split in modern day Croatia, divided the Roman Empire in half, the differences between Europe and the Near East, Christian and Muslim, Eastern and Western Christian, Greek and Latin, Slav and German, Hapsburg and Ottoman, civilization and barbarism, have emerged from the fiery cauldron of what is now modern day Serbia, Croatia, Albania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, European Turkey, and, depending on whether you’re a Serb or an Albanian, a Muslim or an Orthodox Christian, Kosovo.

It’s little wonder, therefore, that Emir Kusturica, who is both the Fellini of Balkan cinema, opened his most famous movie, Underground, with the line “Once Upon a Time There Was a Country.” Yugoslavia, which gestated in the centuries long struggle of the South Slavs against the mighty Ottoman Empire and was birthed by the most consequential assassination in all of history, was gone almost before anybody even realized it was there. What better than a movie, a loud, raucous musical really, to define what it all really meant.

But the cinema of the Balkans is more than Emir Kusturica and more than Serbia. Ever since André Carr, a representative of the Lumière brothers, set up the first movie theater in Belgrade in 1896, Balkan cinema has mirrored the ideological, ethnic, national, and religious conflicts of this turbulent region, down to this very day. Promoting a movie like Jasmila Žbanić’s Vadis Aida, which accuses the Serbian military of a genocidal massacre, or Predrag Antonijević’s Dara of Jasenovac, a devastating account of Hitler’s Croatian puppet regime and the worst concentration camp very few westerners have heard of, is bound to provoke a passionate response on both sides. Romanian cinema, while not as famous in the west as Serbian cinema, still has a tradition that dates back to 1900. Even tiny countries like Slovenia and Albania have produced notable works like France Stiglic’s On Our Own Land and Saimir Kumbaro’s The Death of a Horse.

There are even American and Western European movies like the classic war/heist film Kelly’s Heroes, which was made with the cooperation of the Tito government, and Volker Schlöndorff’s The Tin Drum, not to mention the classic cycling movie Breaking Away, set in the Midwest but written by a Serbian American screenwriter, that can also be considered part of the Cinema of the Balkans.

Quite frankly it is a tradition far too large and complex for a western Anglophone like myself to ever fully master. But it is a tradition worth exploring almost as much as French or American, Soviet or Japanese film, and certainly as important to Eastern European culture as Polish or Czech cinema. It deserves to be better known in the west.

In the Baščaršija neighborhood of the Stari Grad municipality of Sarajevo, near the iconic Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque, the Sarajevo clock

In the 1951 movie Strangers on a Train, one of Hitchcock’s best, a handsome young athlete, social climber, and aspiring

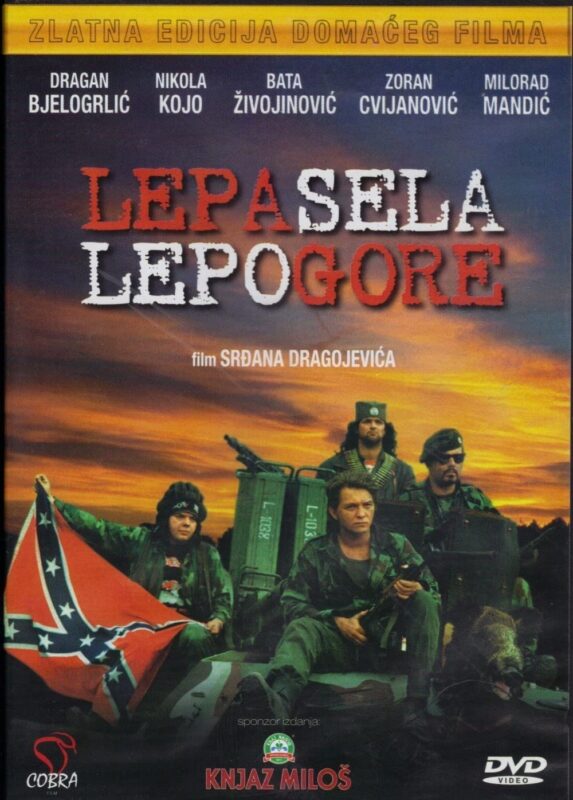

The Yugoslavian Civil War of the 1990s is one of the most poorly understood events of recent history. Beginning with