In the Baščaršija neighborhood of the Stari Grad municipality of Sarajevo, near the iconic Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque, the Sarajevo clock tower rises above the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Constructed in the 16th Century during the administration of Gazi Husrev Bey, the Ottoman Sanjak of Bosnia, who might almost be described as the Ben Franklin of Sarajevo, its height of 30 meters, while not particularly impressive in 2023, towered above the surrounding countryside, and testified to the might of the Sultan in Istanbul. The face of the clock, with its numerals written in Eastern Arabic script, also marks the furthest penetration of Islam into Eastern Europe. Currently it is the only public clock in the world that keeps lunar time, according to which the new day begins at sunset to mark the hour for daily prayers. In other words, in Sarajevo, the evening begins at Midnight. While everything may look familiar, nothing is really as it seems, especially for western eyes.

In late 1944, there were a lot of western eyes in Sarajevo, namely the German occupiers. Nazi Germany was on the run. The Anglo American armies had liberated Paris that Summer. The Red Army had already obliterated the Wehrmacht in Belarus and was barreling towards Berlin. More importantly, Communist Partisans in Yugoslavia had broken out of the German trap at the Battle of Sutjeska, effectively eliminating the possibly of any decisive victory for Hitler in the Balkans. Nevertheless there were still ten heavily armored German division in the former Yugoslavia, all of which were badly needed to slow down the Red Army juggernaut in the east. The problem for the Germans is that while tanks are very useful in battle, they also require a gigantic supply of fuel, especially the bigger German tanks, where you measure gallons per mile, not miles per gallon. SS-Hauptsturmführer Bischoff and Colonel von Dietrich, the Nazi high command in Sarajevo, do have a basic plan worked out. Their tanks have enough gas to get to Visegrad, the site of the famous “Bridge on the Drina” from Ivo Andric’s Nobel Prize winning novel, and there is a large reserve of fuel 114 kilometers away in Sarajevo itself. They also have enough rolling stock to transport the fuel over the gap by train. But they have one big problem, namely Walter.

Played by the Serbian actor Bata Živojinović and loosely based on the real life Bosnian Partisan leader Vladimir Perić, who died in the very last few weeks of the war at the age of 25, Walter has repeatedly baffled the German occupiers, who don’t even know what he looks like. A general insurrection, or even a well-planned campaign of sabotage, could be disastrous for the Germans, and would leave them stranded in a country they had brutalized for the past four years, at the mercy of an angry population, Tito and his partisans. Having been unable to crush the Partisans by force, their only hope is to decapitate it, to cut the snake off at the head, to throw the Yugoslav resistance into enough chaos that they can leave the country in good order. So they turn to a method long the favorite of occupiers and oppressors throughout history, the false flag operation. Unable to defeat Walter, or even outsmart him. They create their own Walter, a German intelligence agent going by the code name “Kondor” brought to Sarajevo from Berlin, who immediately sets himself up as a fake Walter, or to use the German term an “Ersatz” Walter, and begins to recruit his own resistance fighters from among the real Walter’s resistance fighters.

Kondor’s first operation is a specular success. Not only do he and his first recruits manage to blow up a bridge far off the route of the impending Wehrmacht refueling operation, they are “caught” by a Germany army patrol and kill four of them in a gunfight. While Bischoff and von Dietrich are initially a bit dismayed that their special agent from Berlin has killed four German soldiers, they quickly, and cynically, realize the value of the “accident.” The fake Walter now has almost as much credibility as the real Walter, and with the help of a few carefully placed traitors, several of whom are close to the real Walter’s inner circle, he quickly begins generating lists of partisans and resistance fighters who can lead him to Walter and quickly be executed after the are no longer useful to the German Army. He has in fact already accomplished what Bischoff and von Dietrich have laid down as their baseline objective. He has throw the Partisans in Sarajevo into chaos and confusion, more concerned with rooting out traitors and collaborators than with finding out the details of the coming German refueling operation, counterintelligence and security culture now trumping sabotage and resistance.

But the Germans have made a crucial mistake not even they are quite aware of. They have looked up at the Sarajevo clock tower and decided that it’s sunset not midnight, that the day is ending not beginning for the Partisans. The real Walter who also goes by the code name “Pilot,” and who looks a bit like a Balkan Cary Grant, has no idea about the German refueling operation. Bischoff and von Dietrich have overestimated him. They have decided to fight the legend of Walter and not the man “Pilot” and by doing so they have left a trail of breadcrumbs that will lead the partisans right to the train that will transport their supply of fuel from Sarajevo to Visegrad. As Pilot unravels Kondor’s elaborate series of deceptions, as he solves one by one the series of complex puzzles necessary to come face to face with his double, the details of the German retreat emerge in front of his eyes until at least he realizes what they have planned, and strikes one more deadly blow against the German occupiers, leaving their army stranded in the Balkans, and Bischoff and von Dietrich recalled to Berlin, where they will almost certainly be shot for incompetence.

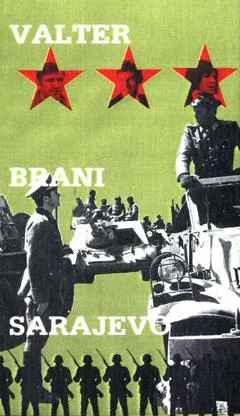

If you are an American or a Western European, you probably haven’t heard of Walter Defends Sarajevo. In reality it’s one of the most watched movies in all of history, mostly because it was one of the few foreign films Mao allowed to be shown in China during the Cultural Revolution. Over the years it has become as beloved in China as Star Wars or Lord of the Rings is in the United States with almost every person in that country of 1.5 billion people either having watched it, some repeatedly, or knowing someone who has. For the Chinese of the 1970s, Walter Defends Sarajevo was not only a glimpse of the far off West. It was also a glimpse of the exotic Near East.

Bosnian director Hajrudin Krvavac was a student of American and Italian movies, of Sergio Leones spaghetti westerns and American action movies like Kelly’s Heroes, Von Ryan’s Express, and the Dirty Dozen. Unlike most of the official culture of Communist China, Walter Defends Sarajevo did not show the world in black and white. There are no lectures about socialism or the proletariat. Walter Defends Sarajevo not only avoids the easy trap of dividing the world into a cartoonish good and a cartoonish evil, the entire point of the plot is about trying to figure out who the good guys and the bad guys are in the first place. If that weren’t enough, you also have to figure out which good guys are pretending to be bad guys and which bad guys are pretending to be good guys. Walter Defends Sarajevo has no shortage of action scenes, but in the end Walter and the Partisans don’t overpower the Germans. They outsmart them. But Walter defends Sarajevo is more than just another 1970s action movie. Not only do the Yugoslavian Communist outsmart the Germans, Hajrudin Krvavac, a religious Bosnian Muslim, or “Bozniak,” outsmarts the Yugoslavian, and in the end, Chinese communists.

Indeed, at first it would seem odd that a film centered around the Grand Mosque of Sarajevo would be allowed into Communist China at all, which to this day censors movies with religious messages. But unlike Star Wars, which rubs it sill pseudo-religious message into the viewers face, on the surface Walter Defends Sarajevo is a purely secular movie, which, unlike East European movies like Andrei Rublev, was not only tolerated by the Tito government, but promoted by the communist authorities. The film was not even reviewed well in Yugoslavia because the film critics of the day were bored by yet another Partisan movie, yet another film celebrating the triumph of communism over fascism. Hadn’t they seen the same movie a million times before?

But the Chinese people saw in Walter Defends Sarajevo something European intellectuals missed. Sure it was an action movie. Sure it was an action movie in an “exotic locale.” But it was also an action movie in an exotic far off locale with heart lurking beneath the shallow exterior, a heart that might have bored the cynical Frenchman or German who had seen one too many Bergmann films, but which was like nectar from the gods for a Chinese man or woman bound by the strict discipline of the Cultural Revolution. Hajrudin Krvavac so dazzled the communist authorities of both countries with shootouts and train hijackings they missed the way he slipped in the soul of the Bosnian people, a people who on the surface look like any other white Europeans but in reality have one foot in the west and another foot in the Islamic near East.

The final sequence of Walter Defends Sarajevo, where Walter and two other Partisans blow up the German fuel train, and some earlier action sequences, a motorcycle chase through the narrow, winding streets of Sarajevo, and a shootout in the Baščaršija neighborhood, are competently done, but compared to most western movies nothing special. If you’ve seen the French Connection or The Great Escape, the action scenes in Walter Defends Sarajevo are not going to impress you.

The the real climax of the movie takes place under the Sarajevo Clock Tower. Sead Kapetanović, played by Rade Marković, who looks a bit like a Balkan Dirk Bogarde, is a dignified, petty bourgeois man in his 50s, a widower who owns a clock and watch repair shop. To all appearances, he’s just another apolitical old man who wants to get through the war and the occupation with his business in tact, and his only daughter Azra, a young women in her late teens, safe. In reality, he’s a long time supporter of the communist resistence. More importantly, Azra, has become involved with the Partisans herself. Sead, who’s well aware of the danger, tries to talk her out of helping Walter and the Partisans, but he’s also a basically enlightened man who knows that she has to make her own decision. At first glance, you might think Azra has become involved with the Partisans to impress her boyfriend, who looks a bit like a young Viggo Mortensen, and his friend, a young Emir Kusturica in his first acting role. But in reality, it’s the opposite. In spite of her youthful innocence, Azra is a highly competent agent for the Partisans, disguising herself as a nurse and helping to steal a wounded Partisan away from the Gestapo while he’s undergoing surgery. Her boyfriend, on the other hand, while well-intentioned, is kind of a fool, letting it slip to the fake Walter that he’s her boyfriend and in the end drawing her into an ambush that kills them both, along with a dozen other young communists.

When the Gestapo lay their bodies out on the town square, daring their families to claim their loved ones and expose themselves, even Pilot/Walter cautions them against it. But family bonds and the love of a father for his only daughter are much stronger than loyalty to Tito or communism or even fear of death. In a very skillfully shot scene which borrows the “jump cut” technique developed by the French New Wave, we watch Saed in the crowd gathered around the dead young communists. He hesitates. Then we see a closeup of his daughter’s body, and then a closeup of his middle aged face, a tear rolling down his check. Finally he defies Walter himself, the legendary leader of the Partisans, breaks out of the crowd and walks towards his daughter. One by one the rest of the crowd follows along until Walter himself joins them, the people leading the leader. The Germans, so flabberghasted by Saed’s indifference to his own death, are baffled. Do they shoot them? do they take down their names and trace their contacts. Finally they decide just to let them go. Perhaps von Dietrich, knowing the war is lost, doesn’t want another massacre on his conscience. Perhaps he’s so transfixed by the integrity and defiance of the people of Sarajevo he’s momentarily frozen.

Saed, on the other hand, an experienced Partisan, knows that he has compromised himself, that when the Germans recover their senses he will probably be rounded up and shot. But Saed has one more act of defiance left. After a courier from the fake Walter manages to bluff him into arranding a meeting with the real Walter under the Sarajevo Clock Tower, Saed realizes it going to be his fate to join his daughter and not see the end of the war. Since there were obviously no cell phones in Sarajevo in 1944, and he has no way of contacting the elusive Walter, he puts on his best tailored, three piece suit, settles his debts, gives one final piece of advice to his teenage apprentice — watch making is a recession proof trade since people will always measure time — takes a 45mm automatic out from behind one of his clocks, and heads down to the Sarajevo Clock Tower. He has accidentally set up an ambush for Walter. Now he will become Walter. Just before meeting with the traitor near Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque he looks up at the clock tower to see a German machine gun nest, knowing it’s meant for Walter, but accepting the fact that it will be his death. “Why are you hear?” the traitor asks, momentarily befuddled. “I have a message,” Saed says. “What message?” the traitor asks? “The last message for you and for me,” Saed answers, beating the traitor to the draw and gunning him down just before he’s gunned down in turn by the German machine gun nest, centuries of history looking down at them all.

The rest of the movie is academic. The people of Sarajevo have defeated the fascist occupiers. Recalled to Germany, and probably his own execution, on a hill overlooking the city, von Dietrich finally realizes who the real Walter is. It’s the city of Sarajevo itself, people like Saed, who love their family and their history more than they fear death.

2 Responses