The Yugoslavian Civil War of the 1990s is one of the most poorly understood events of recent history. Beginning with the 10-Day War in the Summer of 1991, a brief conflict that killed under 100 people and ended with Slovenia gaining its independence, it quickly spiraled into the far bloodier Croatian War of Independence, which killed tens of thousands of people and displaced over 300,000 civilians, mostly Serbs. The Clinton Administration’s decision to bomb Belgrade in 1999, while largely forgotten in the United States, remains a source of bitterness in Serbia, where it’s largely considered a terrorist attack no different from 9/11. In any event, it solved nothing since conflicts between Serbs and Albanians in North Kosovo continue to this day. But it’s the Bosnian war, which took place between 1992 and 1995, and which included the massacre at Sbrebenica and the three-year-long siege of Sarajevo, that’s largely responsible for the villainous reputation that Serbs enjoy in Western Europe and North America.

Even though Lepa sela lepo gore was filmed in the breakaway Republika Srpska, in territory controlled by Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladić, it makes no attempt to deny Serbian atrocities committed during the civil war in Bosnia. Quite the contrary, it rubs our faces in them. The title, roughly translated as “pretty villages burn beautifully,” a quote from Louis Ferdinand Celine’s autobiographical novel Long Day’s Journey into Night, refers to the practice of burning down Muslim villages to drive out, and ethnically cleanse, their inhabitants. But the movie also pushes back against the idea so popular in the United States and Western Europe that the Bosnian War was a simplistic melodrama of good versus evil, of innocent Muslims victimized by bestial Orthodox Christians. Nothing, the director Srđan Dragojević and screenwriter Vanja Bulić seem to be telling us, is ever that simple. Not only are they unclear about exactly “who started it,” they have no real confidence that Yugoslavia was even worth saving in the first place.

Lepa sela lepo gore opens in 1971 at the aptly named Tunnel of Brotherhood and Unity near the Bosnian city of Goražde. The dedication of the tunnel, reported to us in the form of a mock news real and presided over by a local communist bigwig named Džemal Bijedić, is supposed to inaugurate a long reign of multi-ethnic harmony and ethnic progress. But nothing goes as planned. At the ribbon cutting ceremony Bijedić accidentally slices through his own thumb, spraying the girl holding the ribbon with blood, and providing an ominous glimpse of the future. Only ten years later the tunnel has already fallen into such disrepair and decay that Milan and Halil, two young boys, one an Orthodox Christian Serb, the other a Bosniak Muslim, linger outside, staring at the entrance, but fearing to enter because they believe that a Drekavac, an ogre from South Slavic mythology, is sleeping inside, and will destroy the entire village if woken up.

In the Book of Genesis, Cain kills Abel because God rejects his offering. For Milan and Halil, the hatred comes gradually, ominously, like a slight chill in the air that indicates a coming storm. The problem isn’t so much that God favors one brother over the other, but that God is dead, and his children have never quite learned how to get along without him. If at age 10 Milan and Halil looked so much alike you couldn’t tell them apart, we begin to notice differences in their appearance, not subtle but big differences. Milan, played by Dragan Bjelogrlić who looks a bit like a young Russell Crow, is square jawed and masculine. Halil, played by Nikola Pejaković, who almost reminds me of a blond, blue-eyed John Belushi, is round-faced, soft, feminine and pleasure loving but with a terrifying undercurrent of violence just beneath the surface.

If the narrative structure of Lepa sela lepo gore is not quite non-linear, as for example Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp fiction or Srđan Dragojević’s fellow Eastern European Béla Tarr’s masterpiece Sátántangó, then it is fractured, split up into four timelines, each with multiple spoilers that don’t really spoil anything since the film was shot in the Summer and Fall of 1995 while the Bosnian War was still in progress, and released in 1996 right after the Dayton Accords negotiated a tenuous settlement. Like Andrej Wajda’s Man or Iron or Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool it is partly fiction and partly documentary, although unlike Wajda’s film about Solidarity in Gdansk or Wexler’s film about the police riot during the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, it makes no pretense of defining the essential boundaries between history and historical fiction. If Wexler dubbed his own voice over a scene where he’s teargassed in Grant Park warning himself to “watch out Haskell that’s real,” Dragojević inserts footage of Republika Srpska troops burning down Muslim villages overlaid with loud, aggressive rock music as if to ask “is this real?”

Brotherhood and Unity, we already know, will not survive the Bosnian War, by which we can also infer that Milan and Halil’s friendship is also doomed. We also know that Milan will survive until the very end of the film, although whether or not he will survive much longer than that is left in doubt. What we don’t know is why exactly Halil and Milan fell out so bitterly, not just drifting apart, or finding themselves on opposite sides of a Civil War, but taking the whole thing personally, embodying as individuals the violent anarchy that tore Yugoslavia apart.

We first see the adult Milan and Halil playing basketball, which certainly would survive the Bosnia War. Nikola Jokic, interestingly enough, was born the year Lepa sela lepo gore was filmed. We see them drinking in the local Kafana, renovating a garage belonging to Halil, getting dressed up to hit the town and pick up girls. They are, in other words, two very typical best friends in their 20s.

Then the timeline shifts forward. We see Milan in a military hospital, gravely wounded, his body broken but his soul still filled with murderous rage, planning to kill another patient, a Muslim, the administration foolishly put in the same room. Milan has enough life force to keep him alive in agonizing pain, but the civil war has perverted his mind so much that the very strength that allows him to survive, also compels him to drag his crippled body across across a hard, tiled floor to commit murder.

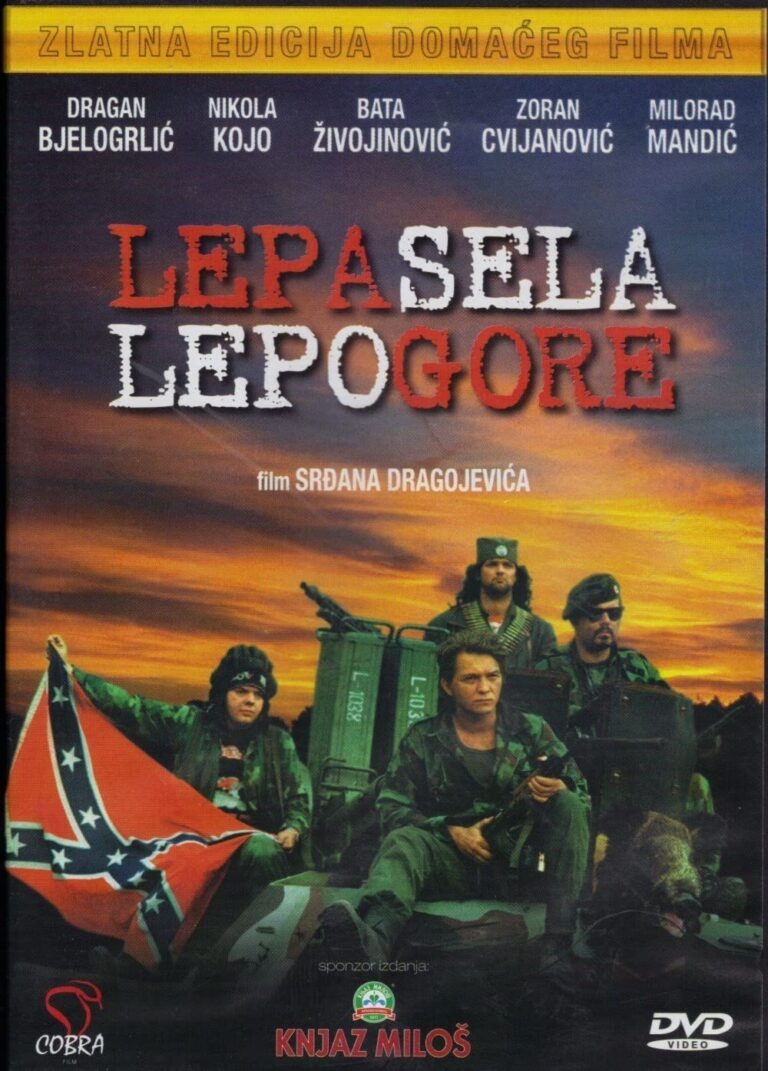

Inevitably as we always knew it would, the climax of Lepa sela lepo gore takes place in the Tunnel of Brotherhood and Unity, with Milan and a small detachment of Serbian soldiers under siege by a much larger unit of Muslims led by Halil. Milan’s Serbian comrades are a cross section of the old Yugoslavia. There’s Velja, a career criminal returned home from western Europe. There’s “Speedy”, a lovable heroin addict. There’s Viljuška, a Serbian nationalist and anti-communist nicknamed “Fork” because he believes the Slavs brought the gift of kitchen utensils to western Europe. Before that the French and Germans ate with their hands. There’s Captain Gvozden, an older man and diehard communist, and Marko, a teenager obsessed with foreign culture who carries a Confederate flag, the meaning of which he may or may not understand. There’s also a clueless American TV reporter who got trapped inside the tunnel along with the Serbs when then shooting started.

The Muslims not only surround Milan and his men, they play psychological games, taunting them over a loudspeaker about their lack of food and water, rigging a cow, a possible source of milk, with explosives, pushing it in the direction of the besieged Serbs, and detonating it just before it comes within reach. If the death of Milan’s mother at the hands of a group of Muslim soldiers we later learn was led by Halil would certainly explain, if not necessarily justify, his participating in war crimes, Halil has no such excuse. As he and his men close in for the kill, the flashbacks tell us little or nothing about why he wants to kill his childhood friend, other than that he believes Milan to have participated in the destruction of the garage he Milan had renovated so many years before.

While Milan has in fact participated in the looting and destruction of Muslims in other villages, he is innocent of any crimes against Halil. Indeed, when he catches a group of Serbian soldiers looting the garage, he machine guns their legs, and leaves them screaming in agony. People in North America and Western Europe often think of the Bosnian War as a conflict between evil Serbs and innocent Bosniaks, but in Lepa sela lepo gore it’s Halil who plays the part of Cain to Milan’s Abel. If someone put a gun to my head and asked me who the movie’s villain was, I would almost certainly say it was Halil. He will eventually commit crimes even worse than his old friend thinks he has done. Later on in the siege, as the Muslims push a traumatized woman towards the doomed Serbs, we not only learn that she’s also rigged with explosives, but that she used to be their teacher in grade school. If Halil never succeeds in killing his brother, he’s guilty of a far graver sin. He kills a symbol of Yugoslavian motherhood out of sheer spite. Even Cain never tried to kill Eve.

While this certainly reflects a pro-Serbian bias on the part of Dragojević, it is also a cry of despair. Western propaganda in the 1990s often depicted Serbian soldiers not only as rapists but as engaging in systematic terrorism against Muslim women. In Lepa sela lepo gore it’s the Muslims, not the Orthodox Christians, who brutalize women. Milan and his fellow Serbs never touch the American reporter even though the United States had already begun to conduct air strikes against the Yugoslavian Army, and they would have considered her their enemy. Until the 1990s, Yugoslavia had been on fairly good terms with the west, who partly saw Tito as a way to chip off support from Stalin and the Soviet Union. The sudden depiction of Serbs as rapists, murderers and war criminals in the middle of a nasty civil war which like any civil war was full of atrocities on all all sides must have been shocking. But for Dragojević the decision of so many of his fellow Yugoslavs to collude with the western powers plotting their destruction must have been worse, and at no time was it stronger than in the Spring of 1995 when they were shooting the film.

In some ways all of the most famous Serbian movies are musicals. If you don’t like brass bands, for example, you will hate Emir Kusturia’s Underground. The moral center, heart and soul of Slobodan Šijan’s classic 1980s film Who’s Singin’ Over There? are two gypsy musicians. During the American bombing of Belgrade in 1999 many people took to the streets as if to dare the hated westerners to bomb them first. Some of them even carried bull’s eyes as if to say “go ahead and kill us you bastards. But you’ll never defeat our spirt.” Looking at old photos from Belgrade in 1999, one sign really sticks with me. “Fuck you yankees,” it said. “Our music is better than yours.” During the entire three months long campaign of terror from the sky, the National Theater in Belgrade gave free performances every night. You can take our lives, the Serbian people seemed to declare, but you will never take our music, our culture, our spirit, our poetry. So it must have been a shock for Srđan Dragojević when that very Spring, in 1995, Davorin Popović, the lead singer of the popular Yugoslavian band Indexi, decided to represent not Yugoslavia, but the newly independent Bosnia and Herzagovina at Eurovision. Imagine Bruce Springsteen declaring loyalty to Osama Bin Laden.

That sense of betrayal betrayal Dragojević felt against Davorin Popović (and no amount of searches on Google will reveal if he was a Christian or Muslim) makes it into the film’s climax. After killing a defenseless cow and murdering their old grade school teacher, Halil does something even worse. He taunts Milan and his men by playing Indexi’s most popular hit Bacila je sve niz rijeku, a tragic ballad from the point of view of a man whose pregnant lover committed suicide, on a loudspeaker. Halil has betrayed not only brotherhood and unity. He has betrayed art and music. He has decided to destroy his friend’s childhood memories. I am shortly going to take your life, he seems to say. I have already taken your music.

But doesn’t quite work. Velja, played by Nikola Kojo, on the surface is exactly the kind of monster the west portrayed Serbian men as in the 1990s, a career criminal who constantly talks about exploiting German women and who makes jokes about raping the American reporter, is so strongly affected by Bacila je sve niz rijeku, the song he insists was playing when he lost his virginity, that he loses all fear of death. “One kiss for a dead man,” he asks the American as he begins to dance to the song’s plaintive strains. As he dies from his wounds, the film drops into a flashback. Why is a man like Velja even in the army in the first place? Yugoslavia still had conscription but a career criminal with a life in the west would have no trouble dodging the draft. Velja, however, had been visiting his mother, and younger brother, at exactly the wrong time, or right time depending on your perspective. When two military policemen show up to drag his younger brother off to basic training Velja offers himself up in his place, his mother and brother playing along with the act as if it had been expected of him all along. If Halil and Milan have betrayed the idea of brotherhood, then Velja, like Jesus, offers himself up as a sacrifice to save his family. The prodigal son has returned, not to be welcomed back into the fold, but to embrace his fate as the family black sheep without bitterness or complaint.

We last see Milan in the hospital crawling across the floor in a herculean attempt to kill a young Muslim. We last see Velja dancing to the song his enemies had tried, and failed, to use to destroy his spirit, knowing that in the end, he had saved his brother from the brutal civil war that would destroy a country that perhaps had been doomed from the very beginning. Velja dies. But also dies knowing that he had saved his brother and in the end his mother and his family. Sometimes criminals turn out to be the best people after all.