In the 1951 movie Strangers on a Train, one of Hitchcock’s best, a handsome young athlete, social climber, and aspiring politician named Guy Haines is stalked up and down the eastern seaboard from Penn Station to Union Station by an obsessed psychopath named Bruno Antony, pursued through Washington DC’s high society by man who is obsessed with the idea that Haines had backed out of a devil’s bargain to “swap murders.” In exchange for Antony killing his first wife, a promiscuous working-class woman from his hometown unwilling to grant him the divorce that would allow him to marry the daughter of a United States Senator, Haines would kill Antony’s father, a severe old tyrant trying to bully his privileged son into getting a job. While of course Haines had never explicitly agreed to the “swap” he also quite “accidentally” gave Antony all the information he needed to find the poor girl and strangle her to death in a secluded wooded area near a local amusement park. It was not only, as Antony insisted, the perfect murder — he had no motive so nobody would suspect him — it allowed Guy Haines to live happily ever after, now married to the daughter of a member of te political elite, his career prospects endlessly bright. Poor Bruno Antony, on the other hand, ends up dead.

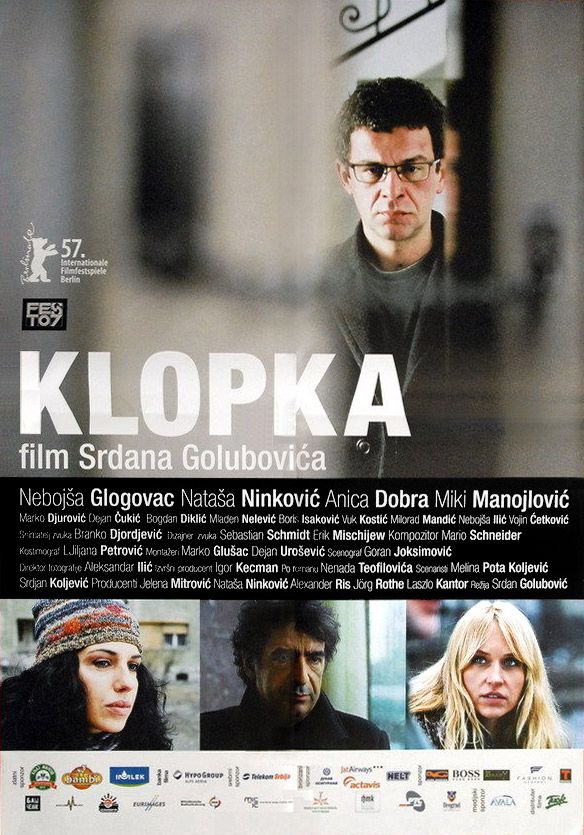

In his 2007 film Клопка, roughly translated as “The Trap,” Serbian director Srdan Golubović stands Strangers on a Train up on its head, telling the story, not through the eyes of the priviliged Guy Haines, but instead from the point of view of the man who does the dirty work, and gets nothing in return. In Golubović’s film we are no longer in Washington DC at the height of the American Empire, but in Belgrade Serbia, the capital of a defeated country that has spent the past two decades being bombed and sanctioned by the United States, and which has now fallen into economic decline. Tito, Yugoslavia and the Communist Party are gone, but they have been replaced, not with democracy but with criminal anarchy. The old Communist Party elite, who were at least competent at running a large city, and who even gave the world some of the most innovative modernist architecture of the 20th Century, have been replaced by vulgar nouveau riche gangsters, people who profit off of society’s woes by contribute nothing except the conspicuous consumption of foreign products, like huge American made SUVs that dwarf the compact, practical cars of the past.

Mladen Pavlović and his wife Marija are a middle-class, professional couple in their 30s, a college educated civil engineer and a high school teacher. While economically they are barely scraping by — she draws a meager state salary and his company is descending into bankruptcy — they are still the happy parents of an 8-year-old boy named Nemanja. Everything seems shabby and run down, but still normal, nothing that a similar couple in New Jersey or Akron Ohio wouldn’t recognize. They take their son to swim meets and root for him on the sidelines. They promise to buy him a cell phone, maybe later when they can afford it, maybe on his birthday. Just about the only thing about Serbian society many Americans would find strange is that the children of the elite and the children of the working class go to the same public schools, not only the same public school system, but the classes. When Nemanja is bullied in a local park by the privileged daughter of a young mother mother around their age, they resent it, but don’t see it as anything out of the ordinary. In the United States, of course, the children of the wealthy and the downwardly mobile lower-middle-class never see one another, but in 2007 Serbia retained enough of its communist past that these kinds of encounters are not only commonplace, but getting worse. Did Mladen Pavlović study hard in high school and get a degree in civil engineering just so his son could be bullied by the wife of a local mob boss?

Then, one day, their life falls apart. Nemanja is diagnosed with a rare heart condition that can only be fixed by a surgical procedure available in the west, a procedure that costs $27,000 dollars, not an exorbitant price by American standards, but an impossibly large sum of money for Mladen and Marija Pavlović. While Klopka lacks the explosive theatricality of John Q, an American film released in 2002 starring Denzel Washington on a very similar theme, rarely have I seen a piece of art dramatize so vividly what it feels like not to be able to save your only child. Serbia did indeed have public healthcare in 2007 but only a poorly funded, bare bones system that did not cover experimental surgery. Pavlović is also ineligible for any kind of loan because he rents an apartment and works for a company that might soon be out of business. Marija puts an add in the newspaper trying to “crowd fund” the money, something that would become common in the United States after the 2008 financial crash and after Obamacare revealed itself to be inadequate, but it’s useless. Serbia is not only a poor country. It’s a poor country in transition. The people who might be wlling to help don’t have the money. The nouveau riche who do have the money couldn’t care less. When Mladen out of desperation goes to an old college friend, a man who has become wealthy building vulgar McMansions, he is politely turned down. But do call me later so we can go out for a drink, the fiend adds breezily, completely oblivious of the desperate situation of his old schoolmate. Just about the only thing the ad accomplishes is to humiliate Marija when one of her students offers to kick a few Dinars her way in exchange for a good grade on the exam. Later, when an even more desperate Marija visits the student at her home to give private lessons, she notices that the very wealthy young girl’s parents own an empty, gold plated picture frame worth over $30,000 dollars. On a whim they have spent more money then it would take to save Nemanja’s life.

If Hitchcock puts the neoclassical architecture in Strangers on a Train, the Jefferson Memorial and the magnificently grand Penn Station and Union Station, to good use to represent the American Empire at its height, there’s something about the empty picture frame that represents post Milosovic Serbia. Yugoslavia had never been a particularly wealthy country by western standards, but it was innovative and complex, a pluralist society that somehow united Muslims, Eastern and Western Christians together in a workable secular harmony. Belgrade had not only been the capital, basically the New York of the Balkans, but a showplace for modernist architecture, not only the famous brutalist skyscrapers every western art critic raves over, but also an extensive public housing system built it the aftermath of the destruction of the Second World War. It wasn’t quite “Red Vienna” but it was a vision of the future a young civil engineer like Mladen Pavlović would have grown up dreaming about. Indeed, one of the film’s great strengths is that it shows and not tells us what architecture must have once meant to Pavlović in his youth. Belgrade is now a frame without a picture, a harsh modernist landscape full of sharp, brutalist angles and abstractions which were supposed to have replaced the traditional culture of the Balkans, but which have not been completed. Except for a young gypsy boy who washes windshields at a street corner which will eventually take on an important role in the plot and a tattered religious calendar with an image of St. George at Mladen’s workplace, this is not the colorful world of Emir Kusturica. It’s a cold, secular, alienated western city mired in the poverty of the east.

Srdan Golubović places no stock in the idea that the family is a refuge from economic hardship. It’s often the opposite. While a single man in his 30s can survive a few bad years, for a father it’s a lot more difficult. Mladen not only begins to feel like a failure unable to protect his children, he and Marija begin to drift apart. She’s careful not to accuse him of weakness or inadequacy but when she snaps at him for doing the dishes because she “does not need that kind of help” it starts to become clear that she’s beginning to think less of him as a man. When someone finally answers the ad Marija placed in the newspaper, and arranges a meeting at the Hotel Moskva, an ornate luxury hotel that predates communist and even the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Mladen is at the end of his rope, willing to try anything. He is met by an unnamed man and suddenly we find ourselves in a Balkan echo of Strangers on a Train. The man, played by the famous Serbian actor Miki Manojlović, is nothing like the flamboyant Bruno Anthony. He’s a subdued middle-aged gentleman with a low key manner who projects a quiet authority, a very familiar if you’ve seen a lot of mafia movies, the senior “made man” who has no time for flashy arrogance but is not above ordering an assassination between sips of coffee. Like Bruno Antony, he has an offer Mladen cannot refuse. If Mladen agrees to assassinate another rich criminal, he will not only for Nemanja’s surgery, but for travel expenses to and from the hospital in Berlin.

If Mladen is horrified by the man’s offer, and brusquely turns him down, the man expresses no dismay. He knows, like the Bruce Springsteen character in his song Atlantic City, that Mladen has debts, or in his case, expenses that no honest man can pay. The next day he calls again. Has Mladen thought about the offer? He should think about it. A day later, Mladen finds a gun, a down payment, and a map giving directions to the residence, an outline of his daily schedule, and a description of the man he is to kill. The target is no innocent. Just the opposite. He’s exactly the kind of nouveau riche gangster who has been sucking the lifeblood from post-Milosovic Serbia, partly responsible for the kind of world that condemns children like Nemanja to death. If Mladen’s communist grandparents fought fascists why should he stay his hand from striking down a man like this? Of course Mladen never tries to talk himself into carrying out the “hit” the way I just did here. Part of Klopka’s strength is that it’s cinema, not theater. Srdan Golubović shows his character’s motivation. He does not write them explicitly into the script. When Mladen finally tracks down his target, and shoots him in front of his apartment building, it comes from a physical, palpable sense of desperation, not as the aftermath of a soliloquy. No. Mladen is not Prince Hamlet. He is simply a desperate man who does what he has to do to save his family.

Bruno Anthony kills Miriam Haines for kicks, and just perhaps jealousy. Mladen Pavlović kills out of desperation, and out of the noble urge to save his child. But once the job is done, both men find themselves in the same position. If Guy Haines never explicitly agreed to kill Bruno Anthony’s father, then he certainly benefited from the death of his wife. Similarly if the man at the Hotel Moskva explicitly promised Mladen the $30,000 in exchange for the hit, it’s not exactly the kind of thing you can put into writing. Mladen has no way to enforce an illegal contract other than going to the police and confessing the crime, which indeed he does, but as Bruno Anthony says, a crime without a motive is the perfect crime, and the police simply kick him out the station with the warning that if he returns and interferes any more with their investigation they will arrest him for obstruction of justice. To make matters even worse, Mladen then discovers that while his victim may indeed have been a ruthless criminal, he was also a father with a wife and daughter who loved him. Not only has he failed to save his own family, he has destroyed another.

Like Bruno Anthony, Mladen decides to stalk the man who walked on a deal they both made. Unlike Bruno Anthony he doesn’t have the advantage of knowing his name. He had met with him once, briefly, in the Moskva Hotel, but that’s all he has to go on to track down one man in a huge city of over a million people. The urban anonymity and alienation that allowed him to commit the perfect crime is now the urban anonymity and alienation that will prevent him from getting paid for the perfect crime he was commissioned to carry out. But the ingenuity and courage Mladen displays in figuring out how to confront the man who cheated him out of his son’s life proves that he’s anything but a coward or a failure. Just the opposite. He has no hesitation pursuing a man he genuinely believes to be a dangerous mob boss. That the man turns out to be something entirely different, simply another Guy Haines who had a problem he desperately wanted to get rid of, changes nothing. Mladen was willing to kill to save his little boy. Now that he’s committed a murder he’s willing to accepts the consequences. The film’s final irony, and indeed this movie has so many unexpected twists that I’ve barely given any spoilers in this review and probably couldn’t even if I tried, leaves you with a crushing sadness. Mladen was a hero who died to save his little boy, a decent, strong man who had been placed by events beyond his control in an impossible situation. One only hopes Nemanja eventually figures out exactly how much his father had been willing to do to save his life.

2 Responses