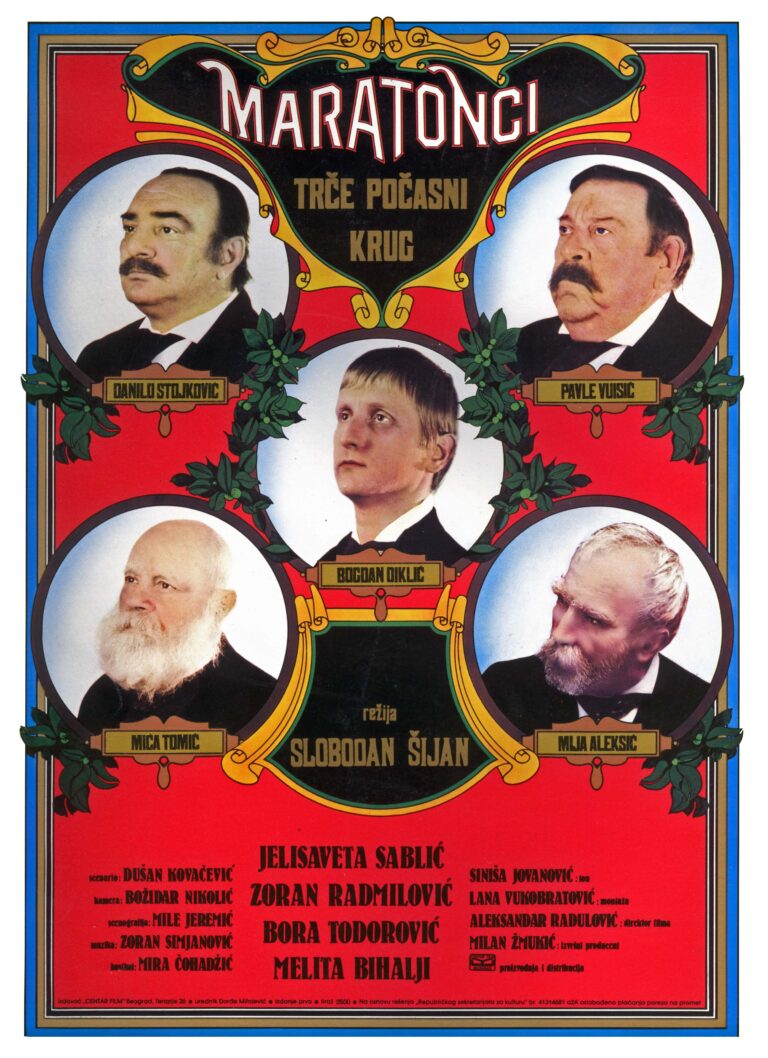

If ever there were a film worthy of an American revival, it’s the Yugoslavian black comedy Maratonci trče počasni krug, the Marathon Family. Released in 1982, two years after the beloved communist patriarch Joseph Broz Tito finally died at the age of 88, director Slobodan Šijan and screenwriter Dušan Kovačević dramatize what happens to a society that lived under a gerontocracy for so long the younger generation has become unfit to rule. The President of the United States is 80. His most likely challenger in 2024 is 76. The leader of the American left is 81, and the senior Senator from California is 89. If this movie proves as prophetic for the American gerontocracy as it did for the Yugoslavian gerontocracy, we are about to learn a very hard lesson, very soon.

This is not an easy film to find. There are no copies on Amazon or Google. Centar Film, the original distributor, has a very nicely designed website, but does not seem to have a copy for sale. Its YouTube channel does have an extensive selection of clips with English subtitles, but important parts seem to be missing. There are also copies floating around on torrents, and while I would normally recommend against it, I doubt you’ll have much trouble with copyright trolls going after you for downloading a 41-year-old film from a country that no longer exists.

The Marathon Family opens in 1934 with the assassination of Alexander I of Yugoslavia by the Bulgarian gunman Vlado Chernozemski. Largely forgotten by history, at least in the west, this was a traumatic event that evoked the specter of another general European war. The British writer Rebecca West was so convinced that it had been masterminded by Benito Mussolini that she actually learned Serbo-Croatian and traveled to the Balkans, where she would eventually write her great book Black Lamb and Grey Falcon. For Dušan Kovačević, who is now a Yugoslavian royalist, the death of Alexander was the end of the dream turned into a reality by the daring act of Gavrilo Princip. Thirty-nine-years later, in 1973, when he wrote the Marathon Family as a stage play, it was clear that the communist dream was coming to an end as surely as the royalist dream had received a mortal blow just before the econd World War. The Marathon Family is above all a warning. If the younger generation does not take positive steps to seize control of the country from the aging patriarch while the aging patriarch is still alive, the country will descend into chaos and eventually bloody civil war.

After King Alexander’s funeral, we find ourselves in unnamed Serbian town. Mirko Topalović, a tall, blond, gangly young man who looks a bit like a Slavic James Cromwell is sitting in a tree with a telescope trying to get a look through an open window. Our first thought, of course, is that he’s a peeping Tom, but no. It’s not that Mirko is uninterested in sex, but what he’s trying to see is not a naked women, but a dying old man. When a priest walks around the corner, and knocks on the door of the house, he knows it’s all over. Mirko, the youngest member of a family of funeral directors, climbs down from the tree, walks over to the house, and preceedes to measure the deceased for a coffin. We notice his feet sticking out of the bottom of the bed, “a very long man” Mirko remarks, taking his measurements and discovering him to be over seven feet tall, or, to be more accurate, long.

When Mirko returns to the Topalović funeral home and family compound, we learn his position in the family, at the very bottom. Laki, his 44-year-old father, doesn’t believe that any man could possibly be 223 centimeters. “Imbecile,” he shouts, slapping his son’s head. “I sent you to measure a man not a giant.” But Laki’s position isn’t much higher. His own father, the 73-year-old Milutin storms into the room and threatens to saw his head off. Milutin’s own father Aksentije is 105 and Aksentije’s Maksimilijan, who’s deaf and dumb and looks like Santa Claus, is 125. The none too subtle point Dušan Kovačević is making is that in the Topalović family, which represents Yugoslavia, and in turn, the entire communist world, the closer you are to death, the more status you have. That, along with the fact that there are no women — women in the Topalović family die young — indicates we are in a corrupt world that has lost all of its vitality, a world that no longer has a future. When Pantelija, the 150-year-old patriarch — his last friend died in the 19th Century — finally dies, the crisis begins. Who will inherit the family business? The answer of course is no-one. The Marathon runner has run the race for so long that he no longer has enough life in him to take the customary victory lap. Pantelija has failed to provide for a successor. He will drag his world down into the grave with him.

If the Marathon Family has no received the same acclaim that other Balkan and East European movies have received in the west, it’s partly because its aesthetics are a bit too subtle for many western critics. While Emir Kusturica’s Underground, probably the best known Serbian film outside of Serbia, is loudly and brashly avant garde — Kusturica is constantly shouting “you are watching an art film” — The Marathon family at first glance looks more like a 1950s B movie or the old TV serial Dark Shadows. But therein lies its greatness. Slobodan Šijan and Dušan Kovačević have quite consciously set their film in 1934, when modern “talkies” are beginning to replace silent movies. Yet he also cast actors who have already put the “movie star” aesthetic of classic Hollywood behind them. If the sets and the black and white cinematography look like 1934, the acting looks like Monty Python, Al Pacino and Robert Deniro, Mel Brooks and Benny Hill, old school Hollywood meets the method meets old school Vaudeville and silent film slapstick. Slobodan Šijan and Dušan Kovačević have distilled the entire history of western cinema into a 90 minutes, a feat that probably could have only been accomplished in Tito’s Yugoslavia, the most avant garde and libertarian of communist states, with its innovative brutalist architecture coexisting with dreams of royalist glory and the Battle of Kosovo.

With the ancient patriarch dead, anarchy, western individualism, has been loosed upon the Topalović family. Laki, for example, has recently purchased a modern crematorium. It’s 1934. Burials are obsolete. Coffins are expensive, unprofitable, and perhaps dangerous. A subplot involves Laki’s use of a local crime family to dig up newly buried coffins and return them to the Topalović funeral home, where they can then be recycled to bury newly deceased customers and keep the overhead low. The problem is that while this has been going on for years, the family has neglected to pay Billy the Python, the local crime boss, and the debt is about to be called in. Laki intends to leapfrog three generations and drag the family business into the modern world. But it’s not Laki who ultimately determines the fate of the Topalović clan. It’s Mirko, the timid, beaten down, and abused youngest member. Mirko becomes the hero, not by virtue of any innate quality he may or may not have, but simply because of his youth.

What will emerge from the chaos unleashed by Pantelija’s death will either be eros or thanatos, sex or violence, creative regeneration or an entropic apocalypse. Mirko is 25-years-old and probably a virgin. But now he’s either going to get laid or he’s going to kill someone. Kristina, however, his choice of sex objects is desperately trying to cling to the past. The daughter of Billy the Python and the organist at the local cinema, she’s dismayed when Đenka, the proprietor, a dapper man in his 30s, upgrades the movie house to play talkies, which turn out to be a massive hit with local audience. With her career as an organist gone — and she was never any good anyway — Đenka encourages her, and Mirko, who he does not consider a worthy romantic rival, to act in a movie that he’s hoping will make his career as a director, a pornographic knockoff of the 1933 film Ecstasy with Hedy Lamarr. Ecstasy was was indeed a gigantic international hit in 1934, mostly because it was one of the first “talkies” to portray sexual intercourse. That it was only from the neck up didn’t matter. Hedy Lamarr’s facial expressions made it obvious exactly what was going on below the waist. It was of course a cheap exploitation flick carried by an extremely sexy leading lady. But for Slobodan Šijan and Dušan Kovačević that’s exactly the point. Hedy Lamarr is the negation of the Pantelija, life not death, sex not violence. An organism is exactly what can save the Topalović clan from the violent apocalpyse, but alas that is not to be.

Kristina is no Hedy Lamarr. Mirko is certainly Aribert Mog, the handsome German movie star who rescues Hedy from her elderly husband and her marriage of convenience, and Đenka no Gustav Machatý, the Czech director of Ecstasy who would actually go onto work in Hollywood, where he would release sanitized remakes of some of the films he made in Eastern Europe. It’s not that Kristina is uninterested in sex. Quite the contrary, she is to act in the film mainly because she’s in love with Đenka. Her prudery is very much an act. Mirko in turn joins the cast mainly because he’s in love with Kristina, who Denka himself can take or leave. Indeed, Đenka’s pretentious rants about overcoming bourgeois morality and about the moral imperative to follow the avant garde, to create something genuinely new, hint at how Kovačević understands that a more innovative, less authoritarian version of communism, Tito’s Yugoslavia replacing Stalin’s Soviet Union, probably won’t work. Even though at his worse Denka is just another sleazy exploitative, arty bohemian like we have in the west he is, for lack of a better alternative, probably the moral center of the movie, and the stand in for Slobodan Šijan and Dušan Kovačević, who probably dreamed of getting out of the Yugoslavian backwater and going to Paris or Hollywood. Oh woah is me, he despairs, I just don’t have the material to work with. Serbia is a poor, backward country full of ignorant backward people clinging to the past where nobody truly understands my genius. Sadly, while Denka may or may not get what’s coming to him, he meets a horrible end. After he climbs into the crematorium to repair the exhaust system — he’s the local tech guy as well as the local artistic genius — he’s instantly vaporized when he asks the 125-year-old Maksimilijan to hand him a tool. Maksimilijan who is totally deaf if not exactly senile just yet flips the switch and instantly vaporizes the hapless Đenka. A pile of ashes, a handful of dust, are all that remain of Denka, the scientific and aesthetic visionary, the would be creative genius who woud save Yugoslavia from its authoritarian stupor.

The climax of The Marathon Family comes with the reading of Pantelija’s will. In a hilarious set piece each member of the family tries to present his own forged will, claiming that Pantelija had left everything to him, only to see his obvious forgery torn up and thrown into the trash. When we finally get to Pantelija’s authentic will, it’s more brutal than we could have anticipated. The late 150-year-old patriarch not only curses his son, his grandson, his great grandson, and his great great grandson to hell, he doesn’t even have the good sense to disinherit them and donate the property to charity, or to Olja the maid, the only woman in town other than Kristina, who has spent most of the film putting up with constant sexual harassment from Maksimilijan in hopes that she’d at least get something. Instead Pantelija leaves all his property to himself, essentially telling his children to fight it out. The patriarch has planted the poison pill that will eventually lead to civil war. Like King Lear he has divided his family against themselves, only in this case with malicious intent. Needless to say, there’s not a Cordelia, a Kent, or Edgar in sight, only a lot of Regans and Gonerils.

The war, which finally, inevitably breaks out, is shocking in its rapid fire violence. Slobodan Šijan has not only skillfully paced his film, 80 minutes of black comedy followed by 10 minutes of uninhibited, all out violence, he’s made it all go down so easily that we can hardly believe it when we see it. We were all laughing too hard to notice what was coming. Mirko’s transformation from a doormat to a man of action is so quick — we have to go back and re watch a few scenes to confirm they really happened — and yet so obviously inevitable that we instantly realize the only thing that will break up the corrupt world of the Marathon Family is violence. The destroyer has come, but in this case it’s a 25-year-old virgin still treated like a child by his father and ignored by everybody else. And yet the final explosion of comic rage and anarchy is not only horrifying, it’s liberating. We see exactly why everybody in Yugoslavia seemed so anxious to kill one another only 10 years later. When you have nothing to live for, at least you have something to die, and kill for. The final image, so different from the rest of the film, indicates that Mirko’s transformation from doormat to killer, for good or bad, has indeed dragged us into an entirely new world, moral, political, but above all aesthetic.

Never has a film crossed the line from Three Stooges slapstick to mass murder so seamlessly and meaningfully.